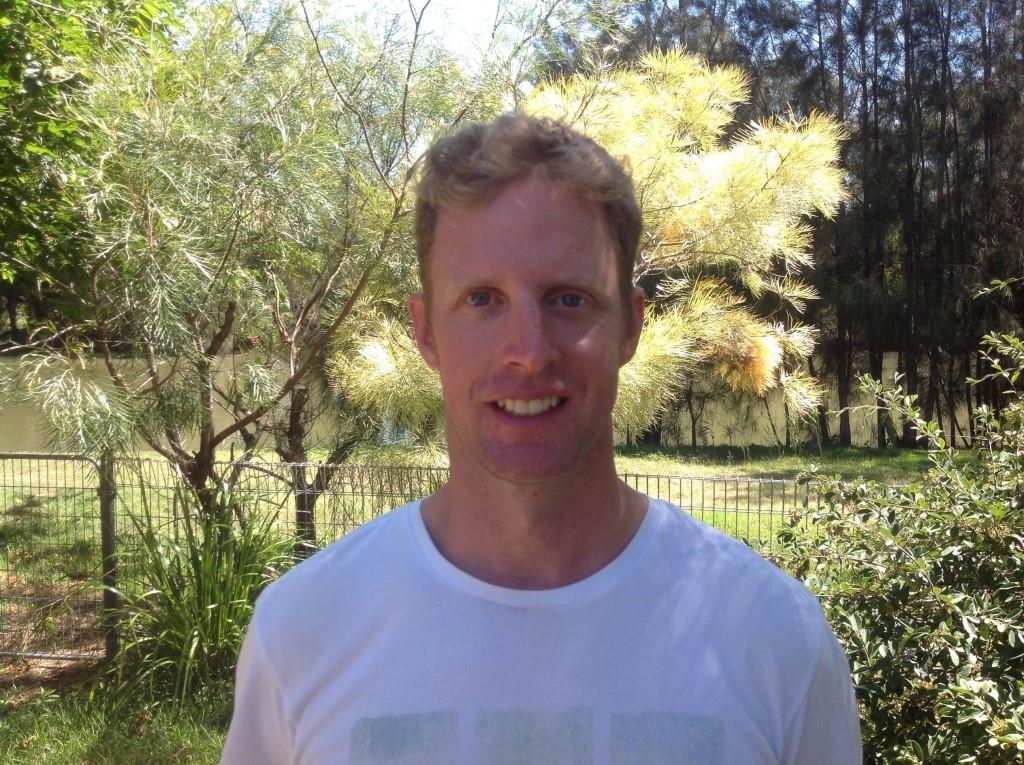

For Stuart Grover, solving big problems has always been second nature. A relentless entrepreneur with a knack for scaling ventures, he has spent decades turning complex challenges into innovative business opportunities. His latest venture, Farmed Carbon, has a mission to fundamentally rethink waste and carbon removal at scale. “Farmed Carbon is my 17th and most ambitious venture,” Grover shares. “Its potential to transform agricultural waste into carbon-negative products really underscores the impact it could have on climate change.” With a background that spans everything from fintech to 3D printing, Grover now brings his expertise to one of the most pressing crises of our time: reversing carbon emissions through cutting-edge climate tech.

If we start seeing waste not as a problem but as a building block, we can tackle climate change while creating new industries and economic resilience.

At the heart of Farmed Carbon’s approach is a modernized take on pyrolysis, a process that converts agricultural byproducts – like rice husks and straw – into carbon-negative materials that can lock away CO₂ for centuries. By integrating microwave technology, the company has found a way to make carbon sequestration not only more efficient but also economically viable for industries that are traditionally hard to decarbonize. The result? An innovative solution that could shift global perceptions of agricultural waste from an environmental burden to a valuable asset. In this conversation, Grover shares his journey, the challenges of scaling climate tech, and why a circular economy is the key to a sustainable future.

What are the biggest challenges climate tech startups face when scaling their solutions, and how can they be addressed to maximize impact?

Stuart Grover: The first major challenge for climate tech startups is the “hardware barrier.” In software, an MVP usually requires just a laptop, some coding skills, and an idea. Climate tech solutions, though, need physical infrastructure and specialized equipment, and that’s where it gets expensive and time-consuming. You can’t just test a concept in the cloud; you have to build actual prototypes, often costing millions of dollars, with long lead times.

Another big issue is moving from a successful small-scale proof of concept to a pilot plant. This typically requires at least a million dollars in capital and anywhere from 12 to 18 months to set up. Early-stage funding at that level is hard to come by, especially in places like Australia where deep-tech investment is still limited. When we were setting up Farmed Carbon, for instance, it cost us over a million dollars and took about a year just to get the equipment we needed to prove our concept.

By turning agricultural waste into stable forms like biochar and pyrolysis oil, we lock away carbon for millennia instead of letting it re-enter the atmosphere.

The next leap is the first-of-a-kind commercial deployment, which usually demands sums in the range of one hundred million dollars or more. Typical venture capital models aren’t designed for these massive, infrastructure-heavy projects, so climate tech startups have to get creative. They often rely on multi-year off-take agreements with governments or major corporations, or they look for government-backed loan guarantees, subsidies, and tax incentives to reduce the risk for investors. Until we see more high-profile success stories in this space, it will remain a major hurdle to secure the funding necessary for large-scale deployment.

Read the full story in the February 2025 issue of Impact Leadership magazine.