James Fitzsimons’ journey into conservation reads like a love letter to the natural world – rooted in his childhood among the grassy Dandenong Ranges of Australia and summer adventures in Wilsons Promontory National Park. Now a Senior Advisor for Global Protection Strategies at The Nature Conservancy (TNC), Fitzsimons has dedicated his career to protecting fragile ecosystems and advancing the ambitious global goal of conserving 30% of Earth’s lands, freshwater and oceans by 2030.

“Often, the most effective conservation happens when we align goals, not just for nature but for people,” he says. With a background in environmental science and a deep connection to the natural landscapes of his home country, Fitzsimons has been a leader of transformative projects that span continents – from restoring shellfish reefs, to partnering with Indigenous communities on land stewardship.

Often, the most effective conservation happens when we align goals, not just for nature but for people.

As the global conversation around a nature-positive future intensifies, Fitzsimons’ insights offer an important perspective on what is required to drive real progress. From pioneering carbon markets in Australia to advancing large scale land protection efforts, he sees partnerships as the cornerstone of TNC’s strategy. Fitzsimons reminds us that lasting change hinges on collaboration – between governments and nonprofits, as well as with local communities whose futures are intertwined with the health of the environment.

Can you share a bit about your background and journey in conservation, particularly your work with The Nature Conservancy? What initially drew you to this field, and what are some of the highlights of your work so far?

James Fitzsimons: I grew up in the forested Dandenong Ranges, east of Melbourne, and developed an early interest in the birds and plants in the area. Summer holidays often involved weeks spent in Wilsons Promontory National Park, the southernmost tip of mainland Australia, which further fueled my passion for natural areas. Studying environmental science at Deakin University, followed by honours and PhD research into public and private land conservation, was a natural extension of this interest.

Before joining The Nature Conservancy, I worked with the Victorian Government, selecting and purchasing properties containing endangered or underrepresented ecosystems to add to the state’s protected area system. These included ecosystems such as native grasslands, woodlands, and wetlands.

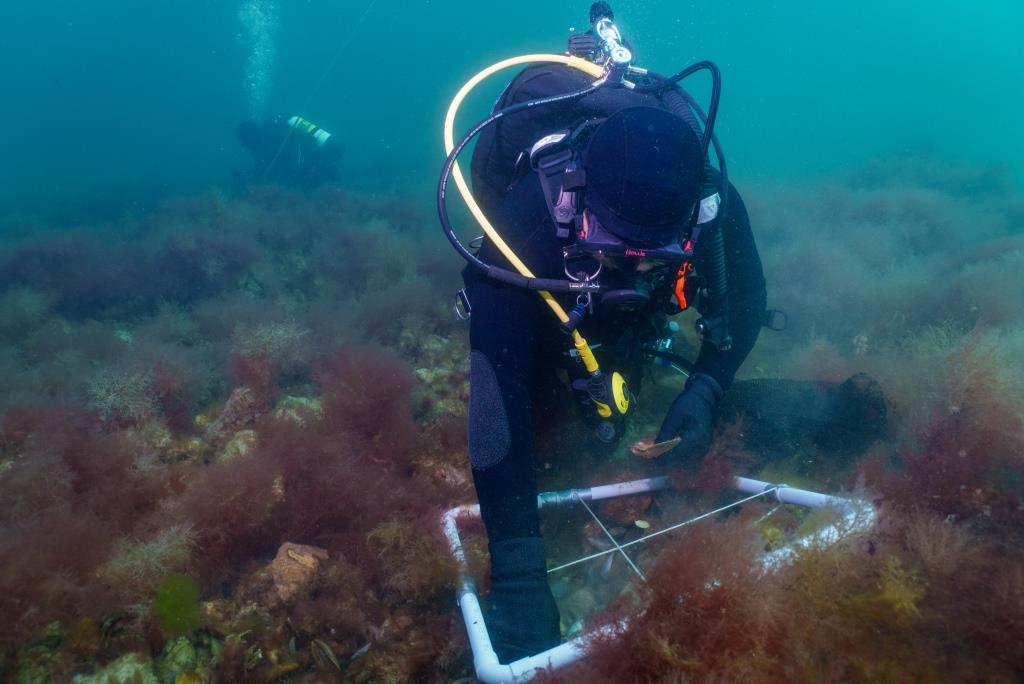

I joined The Nature Conservancy in 2008, heading the conservation and science functions of the organization in Australia. This role was incredibly diverse and rewarding, involving work with Indigenous communities in northern savannas, developing programs to restore lost shellfish reefs in southern and eastern Australia, using markets to restore wetlands in the Murray-Darling Basin, and establishing large-scale protected areas. Collectively, these efforts have resulted in the conservation management of approximately 20 million hectares.

More recently, my focus has shifted to global protection strategies, particularly the ambitious target for nations to protect 30% of Earth’s lands, freshwater, and oceans by 2030.

Lasting change in conservation requires collaboration, not just between governments and nonprofits, but with local communities whose futures are intertwined with the health of the environment.

In your experience, what are the critical elements for building partnerships that not only address nature and climate goals but also create lasting benefits for communities? What strategies do you find most effective for aligning diverse goals within these partnerships?

James Fitzsimons: The Nature Conservancy employs a partner-based approach in Australia and globally, making partnerships a cornerstone of our work.

A key to successful conservation partnerships is identifying joint benefits for all partners, especially when their primary objectives differ. Building and maintaining trust – both at the organizational and individual levels – is crucial, and this requires time.

Recognizing and leveraging the strengths of different partners is also essential. Diverse partnerships can enhance social and political license while enabling communication with wider audiences. However, partnerships require significant time and effort, so it’s vital to assess whether partnering is appropriate for a given situation and to identify the most critical partners.

The concept of “nature-positive” solutions has gained traction recently. From your perspective, how can strategic partnerships help achieve nature-positive outcomes at scale? What challenges have you encountered in ensuring these partnerships maintain a balance between environmental integrity and social impact?

James Fitzsimons: Society still has a long way to go to truly achieve nature-positive outcomes. While strategic partnerships can deliver significant results at scale, areas suffering ongoing nature loss cannot yet be considered nature-positive.

All partnerships involve a mix of environmental integrity and social impact, but the emphasis may vary. For instance, The Nature Conservancy’s shellfish reef restoration efforts in southern and eastern Australia prioritize social benefits such as increased recreational fishing, tourism opportunities, and local employment while also maximizing ecological outcomes. Similarly, assisting Indigenous communities in establishing Indigenous Protected Areas or savanna burning projects has both large-scale environmental benefits and substantial social outcomes, such as income generation and conservation of cultural values.

Other projects may deliver less immediate social benefits. For example, assisting state governments in purchasing properties for new national parks aligns with Australia’s commitment to protect 30% of its lands and oceans by 2030. Social benefits may not be obvious in the first few years as the park is being set up for visitation. However, the social benefits that flow from publicly accessible protected areas, such as job creation in tourism, health benefits, social connection and biodiversity conservation for example, will be realized in the medium-long term.

Partnerships are the cornerstone of our strategy – when we recognize joint benefits, we create lasting impact for both nature and people.

Financing sustainable environmental initiatives remains a significant hurdle. How do you envision sustainable financing models evolving to support scalable and long-term nature-based solutions? Are there innovative models or mechanisms that you believe are particularly promising for a nature-positive future?

James Fitzsimons: We are already witnessing the evolution of sustainable financing in certain systems and regions. For example, Australia’s carbon market incentivizes landholders to preserve native vegetation, while the New South Wales Biodiversity Conservation Trust provides guaranteed annual payments for eligible properties managed for conservation. Additionally, the Australian Government’s Nature Repair Market, set to launch in 2025, offers a promising model.

Sustainable financing, however, cannot rely solely on governments. For instance, the Murray–Darling Basin Balanced Water Fund, developed by The Nature Conservancy and partners, is an impact investment fund that provides investors with commercial returns while ensuring environmental watering outcomes. This model demonstrates the potential for significant capital investment to achieve large-scale conservation outcomes.

However, not all ecosystems are suited to market-based financing. While innovative approaches are valuable, we should not disregard traditional tools, many of which are proven but underfunded. As Valerie Hickey, Global Director for Environment at the World Bank, emphasized at the recent UN Biodiversity Conference: “Look to public funding first, not last.” Governments must recognize natural and protected areas as economic assets and fund them accordingly.

What insights can you share on how conservation strategies are adapting to meet complex local needs while contributing to global environmental targets? Can you share specific examples from your experience that demonstrate how partnerships have navigated these challenges?

James Fitzsimons: Conservation strategies increasingly embrace mechanisms tailored to local needs, which is a positive trend.

Australia has been a leader in this regard. For instance, in the mid-1990s, the National Reserve System primarily consisted of state-managed national parks and nature reserves. Broadening this scope to include Indigenous Protected Areas and private land conservation through conservation covenants has expanded the protected estate from 7% of the continent in the mid-1990s to 22% in 2022. Indigenous and private protected areas now account for more than half of that figure.

A notable example is Gayini, an 88,000-hectare property in southern New South Wales. A partnership between the Nari Nari Tribal Council, The Nature Conservancy, Murray Darling Wetlands Working Group, and UNSW enabled the property’s purchase and return to Nari Nari for conservation, cultural preservation, and sustainable income generation. It is Australia’s largest wetland restoration project, with a permanent conservation covenant guaranteeing $1 million annually in perpetuity to protect 55,000 hectares.

Looking forward, what do you believe are the key steps for advancing collaborative and scalable conservation approaches across different sectors? Are there any emerging trends or practices that you think hold significant potential for accelerating the nature-positive movement on a global scale?

James Fitzsimons: At a global level, the Project Finance for Permanence model is gaining traction. This approach brings together governments, Indigenous peoples, funders, and other partners to secure long-term conservation, sustained funding, and community benefits. Protected areas remain safeguarded because the solutions are collaboratively designed, locally led, nationally supported, sustainably funded, and highly accountable.

Another emerging trend involves sovereign debt conversions for nature and climate. At the recent UN Biodiversity Conference, six international conservation groups launched a coalition to develop practice standards for these mechanisms. Given that 60% of low-income countries face debt-related limitations on conservation, scaling debt conversions could unlock up to $100 billion for climate and nature finance.

Ultimately, while collaborative efforts are critical, addressing the root causes of biodiversity loss requires strong government legislation and enforcement, which are not always collaborative in nature.

Read this story and more features in the January 2025 issue of Impact Leadership – a digital magazine for leaders inspiring sustainability, net zero and impact. Access all magazines here.